The Best Thing for Other People

and how it is not so obvious to think that way

Khuyen is the winner of the Global Drucker Challenge 2015, an essay contest for students interested in learning, applying and sharing the wisdom of Peter Drucker. He is also serving on the Board of Director for South East Asia Service Leadership Network (SEALNet). Currently a junior in Tufts University, he enjoys musing and writing about life and is figuring out how to bring together his gifts to make the most contribution to the world. Khuyen was born in 1993 in Hanoi, Vietnam and he holds a blog at khuyenbui.com. He was speaker at the Octave Program in 2016.

Khuyen is the winner of the Global Drucker Challenge 2015, an essay contest for students interested in learning, applying and sharing the wisdom of Peter Drucker. He is also serving on the Board of Director for South East Asia Service Leadership Network (SEALNet). Currently a junior in Tufts University, he enjoys musing and writing about life and is figuring out how to bring together his gifts to make the most contribution to the world. Khuyen was born in 1993 in Hanoi, Vietnam and he holds a blog at khuyenbui.com. He was speaker at the Octave Program in 2016.

“Khuyen, you would like to have a recommendation letter at the end of the summer, right?”

Mei Lin asked, to which I nodded, timidly. It was our first one-on-one meeting at the beginning of my internship.

“Then the question should be: How do you make it so that writing you a great recommendation is obviously the best thing for your boss to do?”

I must have stood in awe for a long five seconds in front of her. It was one of those “OMG Genius!” moments that makes the whole summer worthwhile.

Let me explain.

As a college student whose homework, exams and papers are the bread and butter of daily life, I was trained to find out what is expected of me and then to meet them. Bringing that mindset to the workplace, I set my intention to do a good job and learn a lot. I thought that if I could do well what my boss wanted then I would have a good letter of recommendation, right?

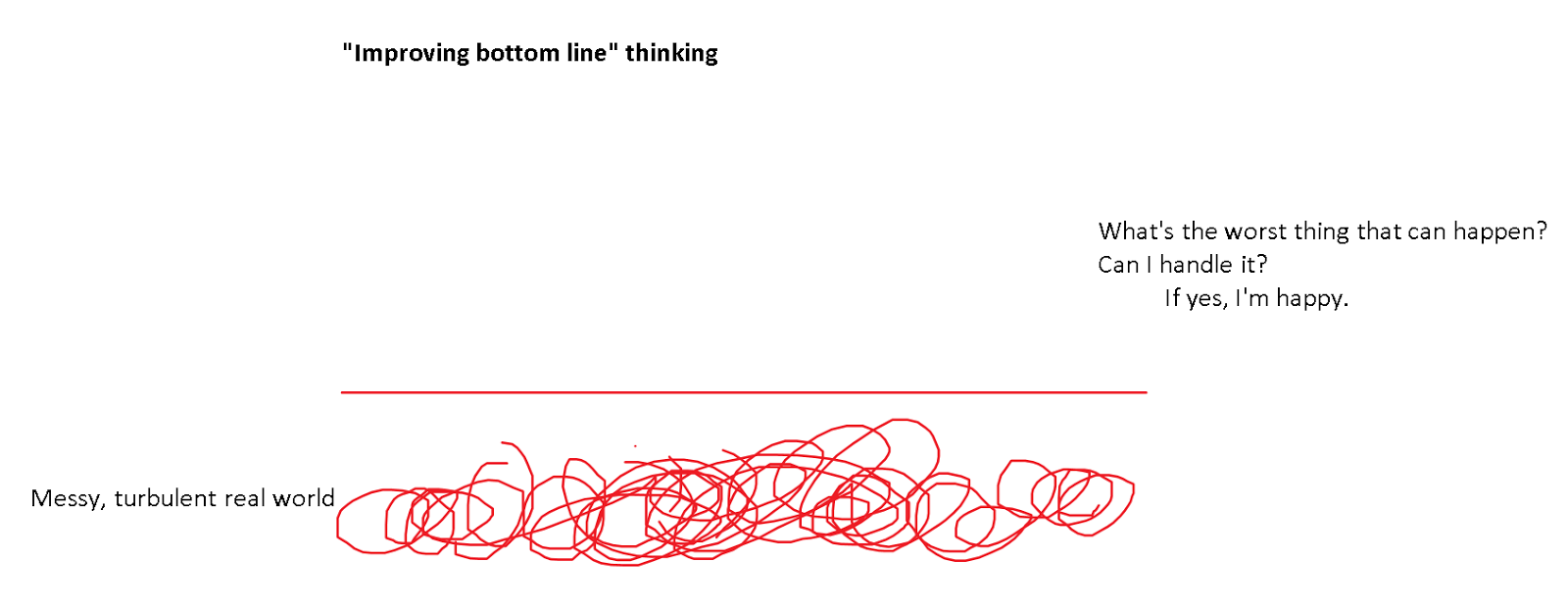

Alas, not so quick. The reality of the working world is rather different. Growing up in a low-income family, I trained myself to be self-sufficient by not wanting or needing a lot. I justified it by this seemingly simple equation:

Happiness = (What I get) / (What I want)

I used to believe in this equation. If I cannot keep increasing the numerator by getting more, I’d rather minimize the denominator by wanting less. My mom taught me since young to be grateful for small things. She always said that to live is already a blessing. As such, I tell myself whenever anything bad happened that it could have been much worse. I call it the self-sufficient mindset, and to be fair, it had helped me a lot. I could stay resilient because as long as I am still breathing, I’m still alive.

This is how I often think.

Before moving on, let’s go back to our one-on-one conversation. Mei Lin continued: “You asked how we could get funding as a new organization. A better question is: How do we make it such that funding us is obviously the best thing for other people to do?” And if this sounds too hard, how do you make it easy for them?

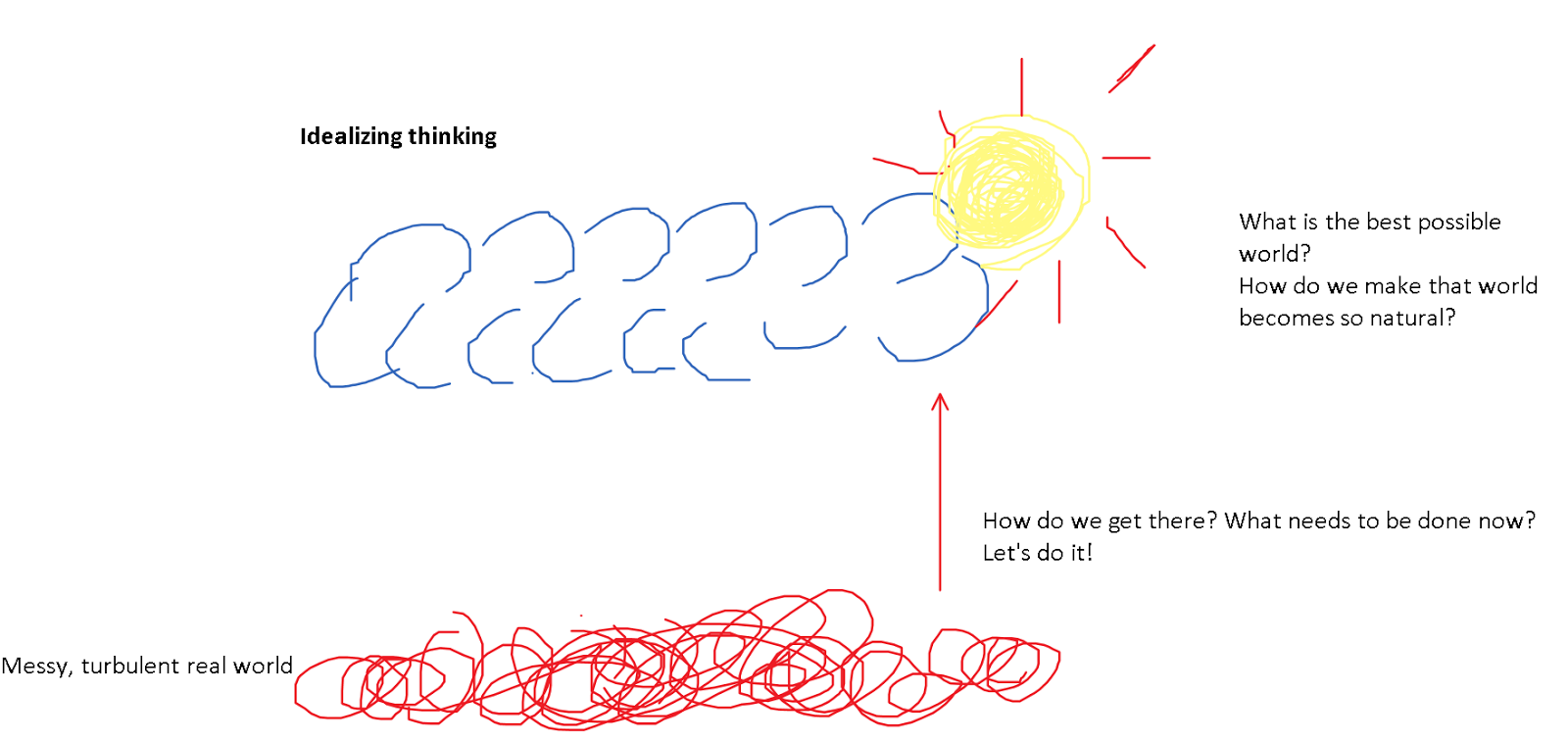

I was awestruck. For someone like me who is so used to “improving the bottom line” mindset, imagining the ideal case feels like moving from black & white to color TV for the first time: wildly inspiring, even borderline scary.

Here is how idealizing thinking is different and complimentary for my old way of thinking.

Previously, my computer science background taught me to think through all the corner cases, to predict how everything can go wrong and plan what to do in each case. In management terms, it’s called “contingency planning”, often reserved for the really smart people who excel in modeling the futures, analyzing each in excruciating details and then optimizing for best possible outcomes.

Yet once I could sit down and think through her questions, I started appreciating its power. First, it shifts my perspective to see from her side. Consider the recommendation letter example: how could it be her best interest to write a good letter for me? Out of reciprocity, that I’ve done a good job so she would recommend me in exchange? Or out of good will, that she wants to help a young person with some potential? Or even bolder, out of her interest that I’m so good she would want to have her name associated with mine? Even writing the last statement made me cringe. It’s so bold: who on earth do I think I am?

Second, it excites and frees up our mind to think more expansively about the bigger picture. Since then, I’ve been applying this way of thinking and asking a different kind of question. For example, instead of “What is the least amount of work to do to achieve the most result?”, I ask “How do we make it such that working is so much joyful and meaningful that we all love doing and do our best? What are some desired properties of such a working environment?” From that idealized vision, we can work backward.

It took me a long time to unlearn my ingrained pattern of thinking, and I don’t promise an easy fix. What I can testify from experiences though is that this way of thinking using the language of ideal, possibility and a positive vision is immensely motivating. I feel that I can do a lot more for the world and be a lot more for people around me. It’s not over-the-top wishful thinking for some probable future scenarios. It is asking for what we desire to have night now. The more concrete our vision of what our world could look like, the more we are inclined to commit and act on it. People often say “With power comes responsibility”. What I have learned is that “Take responsibility and you will have power”. That immense sense of freedom could start immediately the moment we choose to ask a different question. It is indeed is the quality of our question, not the answer, that determines the quality of our life.

Share this Post